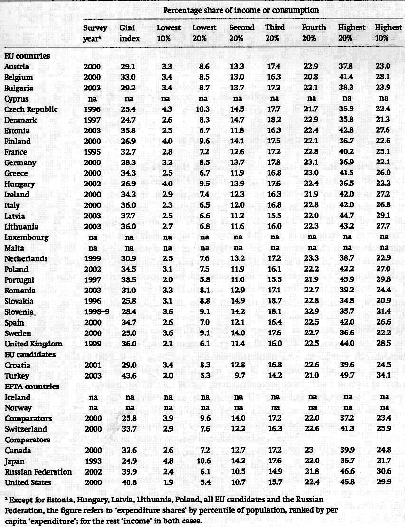

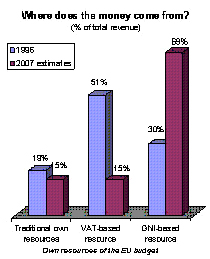

Figure 1: Income distribution. (Source: El-Agra, Ali, ed., The European Union. Economics and Policies, CUP 2007, p. 103)

soziales_kapital

wissenschaftliches journal österreichischer fachhochschul-studiengänge soziale arbeit

Nr. 2 (2009) / Rubrik "Nachbarschaft" / Standortredaktion Wien

Printversion: http://www.soziales-kapital.at/index.php/sozialeskapital/article/viewFile/112/147.pdf

Susanne Wurm:

Preface

After lecturing for a couple of years on "European Social Policy, Migration, Multiculturalism and Interculturality" in the Erasmus and Socrates lecturer exchange programme of the European Union at the universities of Stockholm, Rome, Ljubljana and Oulu in Finland and after having taught "European Economic History" and "European Union Development" at Universities of Applied Sciences in Vienna since 1998, I decided to attempt an analysis and a comparison of the economic, social and cultural aspects of the European Union development from the point of view of a social and economic historian. By interviewing Austrian professionals from different fields of work, covering music, art, medicine, psychology, legal and educational research and banking, I attempted to find reasons for the sceptical attitude of Austrians towards the European Union as expressed in the latest Eurobarometer 2008.

The intention of this working paper is to provide students and a general public interested in current developments in the European Union and their historical roots with a concise overview and a critical comparison of the economic, cultural and social developments of European Union integration and their impact on the satisfaction of European citizens with the state of the Union.

1. Introduction

"Si c'était à refaire, je commencerais par la culture" ("If I were starting over, I would begin with culture") Jean Monet

Whether Jean Monet really said this or not, it is a fact that he and Robert Schuman started with the economy and the preponderance of the economic integration still characterises the European Union today. Nevertheless, Monet's quip epitomises the importance of culture in any form of unity in Europe.

The virtues of Europe today as compared to the United States are the emphasis on trans-nationalcooperation, not only on an economic level, and the humane attitude to law, society and the environment. But Europe has lost a sense of purpose. The EU was built institutionally, not democratically; it would probably not even have come about if there had been national votes on establishing a union after World War II. Nowadays you cannot go around public opinion, and it seems to be fashionable in Europe today to oppose the EU. Politicians exploit the EU for their purposes without considering the costs, as they just take the benefits of the EU for granted. There is definitely a lack of direction. The EU as an ideal is no longer supported by the majority of Europeans, not even by the new members in Central and Eastern Europe. They rather imitate the American way of life, especially the economic and consumer aspect of it, and the focus on the virtues of Europe has got lost in recent years. In Western Europe many people are either supporters of the neo-liberalist American approach or they take up a crude anti-Americanist stance. Yet the EU is the only model of peaceful and economically successful cooperation we have that embodies a sense of collective interest, regulates the market and induced nation states to abdicate some of their sovereignty to build common institutions.

Can a further integration of Europe be achieved today by the common will of the countries concerned? Should it? Will the governments make concessions and sacrifice more of their sovereign rights? Or will Europe be unable to catch up with the interdependent world of today and the future and continue to believe that nationalistic self-interest still makes sense or that European nationalism can carry on where the nation states of Europe were forced to leave off? Those building Europe today never seem to go beyond the purely highly technical level of specialists who are brilliant experts and indispensable, but not understood by the people living in Europe. Yet we misunderstand Europeans if we give them sums and statistics only, which look wan alongside the waves of enthusiasm that have enlivened Europe in the past. Can a European consciousness be achieved solely through statistics? It is disturbing that Europe as a cultural ideal and objective is the last item on the current agenda. No one is concerned with a mystique, an ideology. Europe will not be built unless it draws on the old forces that formed it in the first place and are still lingering below the surface. "The Europe of the peoples" will have to work with the people or they will overturn it with their historical taste for revolution and cast it away.

The disappearance of national frontiers in the movement of goods, capital, services and people could forge a new kind of peoples who feel for instance Austrian and European. The community has been formed largely to avert a return to a tragic past and less to build a clearly envisioned future. So Europeans are bound together by the unpleasant memory of their national antagonisms and their desire to keep those at bay, and now increasingly by a common fear of being run over by waves of immigrants and being wiped out economically by globalisation. Yet the European Union could become a model of how independent states integrate and cooperate. To adapt Churchill's famous remark about democracy: "Democracy is the worst form of government - except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time", the European Union is the worst possible Europe, apart from all the other "Europes" that have been tried from time to time.

2. The Historical and Cultural Concept of Europe as a Unity1

2.1 Why did Anyone ever Think of Europe as a Separate Continent?

By definition a continent is a stretch of continuous land clearly bounded by the sea or at least a narrow isthmus, but Europe is a large peninsula projecting from "Eurasia" at its western side. So why did anyone ever think that Europe was a continent and why do people still think that Europe is a distinct entity?

Since the second millennium BC Greek sailors had sailed up the Bosporus to trade on the coast of the Black Sea. "Europe" was the land on their left, to the west, when sailing north, where most of them lived and "Asia" was the land on their right, to the east, with Troy, Milet and the Lydians, Phrygians and Persians. They supposed that Europe was really separate from Asia. A map of the world of the Greek geographer Hecatheus from around 500 BC shows that he assumed that the Caspian Sea stretched out into a great ocean dividing Europe from Asia. In the wars of the Greeks against the Persian Empire the Persians were seen by the Greeks as forces of barbarism, lacking the capacity for self-government and a sense of freedom. The Greeks labelled this distorted picture of the people on the Persian side "Asia" and by a brilliant piece of propaganda Herodotus reclassified the Greeks "on the Asian side" as really "people of Europe", namely the bearers of independent-minded rationality, law and freedom. This was the moral justification for the imperialist colonising activity all around the Mediterranean. In this way the Greek sailors' idea of Europe "as the land on the left hand side as you sail north" was filled with meaning and propaganda. It became a label for an ideal centred in Athens, where cultural characteristics which were thought of as ideal European ones were most fully developed, while other parts of Europe only participated in this ideal by sharing the cultural values of this European centre. Not only was Europe from its beginning defined in opposition to "non-Europe", but the idea was promoted that Europe's true character was that of its centre and over the centuries this centre moved from Athens to Rome and then to Western Europe. From the Middle Ages on this centre was defined in the terms of Christianity. So Europe was always a word used by Europeans to boost their own image and power and not just to label a certain piece of land.

Even after it had been discovered that Europe was a peninsula of Eurasia and did not deserve to be called a continent geographically, people stuck to it because it signified more than a piece of land, it denoted an ideal, a certain kind of civilisation. Nevertheless they disagreed widely over the centuries and in different regions what exactly that kind of civilisation was. Furthermore it is noteworthy that Europe has no true eastern boundaries except arbitrary ones, such as the Ural Mountains.

2.2 The European Civilisation

Historically, the West looked to Rome, the East to Constantinople. The major separation in the 9th century was the success of Cyril and Method in preaching the gospel to Slavs and shaping the future along Greek Orthodox lines. A later division occurred between North and South with the Protestant Reformation, which curiously split Europe roughly along the ancient Roman limes.

The Eastern Mediterranean had been endowed with a very old civilisation, when the Western Mediterranean was still primitive. After the break-up of the Roman Empire, Europe developed a feudal civilisation and in the 11th and 12th century a lively feudal regime, a particular and very original political, social and economic order. There could be no feudalism without the previous fragmentation of a larger political entity, the huge Carolingian Empire, the first "United Europe". Despite this political compartmentalisation, there was a convergence in European civilisation and culture. There was, indeed, a single Christendom and a civilisation of chivalry, the minstrel, the troubadour and courtly love. The crusades expressed that unity as they were mass movements, collective adventures. The social pyramid with its obligations, rules and allegiances mobilized economic, political and military strength and enabled the West to survive and safeguard its old Christian and Roman heritage to which it added the ideas of the seigniorial regime. Yet all that mattered in this compartmentalized world was the small unit, the narrow, limited native region.

The history of Europe has been marked everywhere by the stubborn growth of private "liberties", franchises or privileges limited to certain groups, big or small. This process has never been peaceful, yet it is one of the elements that explains Europe's progress. The peasants were among the first to begin to be liberated, but certainly the last to be fully free. With the economic awakening of Europe in the 10th century, the increase in population and agricultural production and the growth of towns, the lot of peasants rapidly improved. Money rent started to replace serfdom. These liberties had no firm legal basis. The lord continued to enjoy superior rights over the land and could recover his oppressive powers, which resulted in a succession of peasant revolts. Newly acquired privileges were called into question again with the capitalist economic development beginning in the 16th century. When capital faced economic recession, it turned back to the land in a large-scale seigniorial reaction. The capitalist landowners looked for profit, the small-holders became indebted and so their land could be seized and bond-service increased. This development was especially tragic in Central and Eastern Europe. This system persisted until the 19th century in the East and was responsible for the economic backwardness of these areas. In the West favourable changes began in the 18th century, first in England. Then the French Revolution freed peasants at a stroke, which was copied elsewhere during revolutionary and Napoleonic wars.

The towns were the motors of Europe's first advance and were rewarded with liberties. After a long decline of Roman towns in the West, from the 11th to the 13th century the towns experienced a remarkable renaissance, they prospered and were ahead of their time. Free cities emerged early in Italy and the Netherlands. Medieval European towns were exclusive, their citizens were privileged by virtue of their citizenship. The countryside around them was often under their control, but they were not politically open to the surrounding area like ancient city-states. The liberty of the cities was threatened when the modern states grew more powerful in the 15th century. A territorial economy grew up, replacing the urban economy, but still controlled by the towns.

The territorial states were late-comers to Europe. The ancient form of feudal kingship took a long time to be transformed. The turning point came in the 15th century especially in areas where the urban revolution had been least marked; not in Italy, the Netherlands and Germany where there were so many free, rich and economically active towns. Modern monarchies developed in Spain, France and Britain with a new kind of rulers. Territorial states were served by functionaries, servants of the state. They enjoyed the loyalty of the masses, who saw the monarch as their natural protector against the church and the nobles. The modern state arose from the new costly needs of war. It did not recognise any higher authority, not the Holy Roman Emperor, not the pope. The new nation state wanted to be isolated, uncontrolled and independent. As the modern state tightened its grip, European civilisation became territorial and national. At the heart of these larger civilised entities, the capital cities played an important role and London for instance virtually became England. A redistribution of liberties, granted by the state set in. Liberties were handed out to powerful groups of privileged people by the monarch.

The intellectual ferment of the Renaissance and the Reformation laid the basis for individual freedom, respect for the greatness of the human being as an individual. Effective market economy and money from the colonies upset and weakened the old hierarchies. A certain freedom of choice was discernible, but on the other hand the state imposed a new order which strictly limited such freedom. In the name of the interests of the whole society the state undertook a strict regime for the poor in the 17th century. Already in the 16th century the beggars of Paris were arrested and forced to work in the sewers, chained together in pairs. Throughout the Middle Ages the poor, vagrants and the mad had been protected by the Christian right to hospitality and alms, they were viewed as God's emissaries, yet people were keen on sending them on their way rather than keeping them within the city walls. A certain form of liberty prevailed; the peasant could flee his lord for another one, go to the city, to the New World or become a soldier. Even the Elizabethan Poor Laws in England offered some scope for humane treatment of the poor. With capitalism all these people became enemies of a society which was urban, capitalist and attached to order and efficiency. Throughout Europe the poor, the sick, the unemployed and the insane were locked up, sometimes with their families alongside with delinquents. A large number of establishments were founded for this purpose, barracks with forced labour.

The French revolution itself did not succeed in establishing complete liberty. Hence liberty was invoked by almost all the ideologies and claims that advanced in the 19th century: "liberalism". Freedom of thought necessarily implies the idea of tolerance and respect for others. The revolutions of 1848 were a crucial landmark for liberty and electoral reform. "Liberalism" is now virtually banished from active politics, yet it remains part of Europe's heritage and has become second nature. Any breach of individual liberties affronts Europeans. In the face of authoritarian states a certain kind of defiant, anarchic liberalism continues to survive as a Western heritage.

The spiritual and intellectual life of Europe was always subject to violent change, yet that should not distract from an impressive continuity of Europe's thought, evident throughout all its successive phases.

First, "Christianity": Western Christianity was and remains the main constituent element in European thought, including rationalist thought, which although it attacked Christianity was also derivative from it. A European, even if he/she is an atheist, is still the prisoner of an ethic and mentality which are deeply rooted in the Christian tradition. Christianity became the official religion in the Roman Empire as a result of the Edict of Constantine in 313. With the 18th century there was a great reverse. This time material progress did not serve the cause of the church, it went with a scientific and philosophic movement which on the contrary opposed the church in the name of progress and reason.

Second, "Humanism": European thought is inconceivable except in the context of a dialogue with Christianity, even when the dispute is violent. This context is essential to the understanding of humanism, one of the fundamental aspects of Western thought. Humanism frees and magnifies humanity and diminishes the role of God even if not completely ruling it out. Humanism is a manifestation of human pride, directed against exclusive submission to God, against a wholly materialist conception of the world, against any system that would reduce human responsibility. Humanism is a constant drive towards ways in which it can modify and improve human destiny. It signifies a European quest for what is new, difficult, forbidden or even scandalous, with many achievements and many set-backs.

Renaissance humanism of the 14th and 15th centuries on the one hand, represented a dialogue between classical and Christian civilisation. Pagan Rome had never died out in the West, Christian Europe was on a day-to-day contact with ancient Rome and its traditions, classical heritage had entered language, thought, literature, urbanity and monasteries. The Renaissance then distanced itself from medieval Christianity in its approach to life itself, by creating an atmosphere of lively enjoyment, relishing the pleasures of the eye, the mind and the body. It was on earth that people had to build their kingdom.

On the other hand there was Protestant humanism, starting in 1517 with Luther's propositions. It was the source from which the great flood of Reformation flowed between the 15th and the 16th century. The following excesses of war and violence died down in the 18th century, but Protestantism survived and today is widespread in a large part of the Western world. The nature of Protestant humanism despite its great diversity becomes evident once it is contrasted with Catholicism. Common is an inclination towards the free study of the Scripture, historical criticism of sacred texts and a kind of deist rationalism, greater freedom of conscience in the spirit of Enlightenment and under the influence of scientific progress. This might have helped Europe to develop towards a greater independence of the mind together with the general evolution of philosophical and scientific thought in Europe.

If we look at the humanism of the French Revolution, we can see that Europe has always been and still is revolutionary and at the same time counter-revolutionary. What revolutionary humanism essentially believed was that violence could be legitimate if it were used to defend law, equality, social justice or the mother country. But to embrace violence was acceptable only if it were the sole means of making the society more human and fraternal. Revolution meant violence in the service of an ideal. The counter-revolution sprang from the same roots, but its historical failing was that it looked backward and tried to move backward. It is remarkable that "1789" inspired mass workers' movements in the 20th century and it is still alive.

Finally "scientific thought": The problem is to discover why modern science developed only in the context of Western civilisation and not much earlier in advanced civilisations such as China and Islam. All scientific proceedings are undertaken in the context of a certain view of the world. There can be no progress, no reasoning and no fruitful hypothesis if there is no general set of references to locate one's position and choose one's direction. At the beginning of the 18thcentury the unprecedented economic growth affected the whole world, but its centre became Europe, so industrialisation and the increasing demand caused by material and technological conditions were the motors of change. In that way, one Western phenomenon, namely science, has to be explained by another Western phenomenon, namely industrialisation. These two go side by side. Much earlier than the West, China possessed the rudiments of science in an elegant and advanced form, but it failed to reach the decisive stage, because it never experienced the economic impetus, the capitalist tension that spurred Europe on. The beginnings of this creative tension can be traced back to the great medieval trading centres.

2. 3 The Unity of Europe

Europe simultaneously enjoys both unity and diversity. Among the things shared by the whole of Europe are, as we have seen, its religion, its rationalist philosophy, its development of science and technology, its taste for revolution and social justice, and its imperial adventures. At any moment however it is easy to go beyond that apparent harmony and find the national diversity that underlies it. Such differences are abundant, vigorous and characteristic of Europe as such. But they exist just as much between the north and south of France, Italy or Germany.

One of Europe's shared characteristics is its outstanding art and culture. But that does not mean that all nations of Europe have exactly the same culture. Yet any cultural movement that begins in one part of Europe tends to spread throughout the continent. This cultural phenomenon may face resistance and rejection in one part and be successful in another part of Europe. Nevertheless Europe is, broadly speaking, a fairly coherent cultural whole. Every cultural centre in Europe has always attracted artists, philosophers, scientists from various parts of Europe. One can mention the wanderings of Italian Renaissance artists or the "commedia del arte" actors groups that travelled as far as England at the time of Shakespeare, or the spread of the Italian opera from Florence in the 16thcentury.

For centuries Europe has been bound together by a common economy. At any given moment its material life has been dominated by particular centres of privilege and influence. During the later Middle Ages the centre was Venice, with the beginning of modern times it moved to Lisbon, then Seville and Antwerp, in the 17thcentury to Amsterdam and then to London. Each time the European economic centre was the more influential because not only European economic life centred there, but also the economic life of the world. In 1914 London was not only the great market for credit, maritime insurance and reinsurance, but also for American wheat, Egyptian cotton, Malayan rubber, South African gold, Australian wool, Middle Eastern oil. Very early on Europe became a coherent material and geographical whole, with an adaptable monetary economy and busy communications along its coasts and rivers and via the carriageways and roads for pack animals. This interdependence is the reason why the different regions of Europe were affected almost simultaneously by the same cycles of economic change. In the 16thcentury, for instance, a huge price rise began in Spain as a result of the sudden influx of precious metals from America. The same price inflation affected the whole of Western Europe and penetrated even as far as Moscow, then the centre of a still primitive economy.

Yet all of Europe did not develop at the same rate. A line could be drawn from LÜbeck or Hamburg through Prague and Vienna as far as Trieste, to divide the economically advanced Western part from the economically backward areas to the East. Socially, the separation became evident in the persistence of serfdom among the peasant population in the eastern parts of Europe at a time when it was long abolished in the West. Three important Western European developments reached Eastern Europe much later and they were less prominent there, namely the urbanisation of the Middle Ages in the 10thand 11thcenturies, the Enlightenment of the 17thand 18thcenturies and the industrialisation in the 18thand 19thcenturies. Nevertheless also in the West there were growth areas in the midst of less developed regions. Indeed there can be no economic interdependence unless there are differences of development, in which some regions lead the way and others follow. Despite the national and regional differences economic links have long bound Europe together.

Yet in building European unity politics has always been most hesitant. The truth is that all of Europe has long been involved in the same political system, from which no state could escape without grave risks to itself. But that system did not encourage unity in Europe, on the contrary, it divided European countries into groups of varying membership, whose basic rule was to prevent any hegemony. Each state pursued its own selfish ends and if it was too successful, it sooner or later found the others lined up against it according to the "European balance of power". The growing power of states made this imperfect balancing act ever more dangerous. The ultimate outcome was always war. Until the 20thcentury, the world was at the mercy of this European balance of powers.

Political unity by force always failed, as can be seen from the failed attempts of Charlemagne, or the emperor Charles V. His dream was to conquer all the Christian lands, as his "Imperial Idea" was rooted in the historic Spanish crusade. The emperor lacked nothing, he had troops, excellent commanders, loyal followers, the support of great bankers, the Fuggers, excellent diplomats, mastery of the sea, and he had the treasures from America. It was the "concert of Europe" that defeated Charles V using every method including an alliance with the Sultan.

2.4 Defining European Identity

The German chancellor Otto von Bismarck was of the opinion that Europe was a mere geographical expression. But Europeans, on the contrary, have long been conscious of their civilisation, their continent, its boundaries, topography, languages and ideas. More than any other continent Europe has been obsessed with its own self-definition, with ascertaining just what it is that binds Europeans together and distinguishes them from others. But Europe has had a chequered past. In the medieval urban renaissance, which saw the spread of universities and city states, throughout the Enlightenment and again since 1945 it has been common practice to think and talk European. But at other times much more attention was paid to local interests. Even when Europeans did invoke the idea of Europe they frequently had different things in mind.

There has always been a Mediterranean Europe, an Atlantic Europe and a Northern Europe. For many centuries there has further been a mainstream Europe defined by wealth, trade routes and established political regimes and a marginal one defined by poverty, vulnerability to invasion and imperial domination. And cutting across these lines there has always been the distinction between centre and periphery.

Then there is the important element of size. The dimensions of European states vary greatly. Populous states with long-established, secure state systems, like France and Britain, have always been wary of being absorbed anonymously into pan-European projects, whether led by popes, emperors or bureaucrats. For Europe's smaller countries the situation is quite different. Vulnerable small countries like those of Central Europe or the Netherlands and Belgium can best maintain their distinctive cultural identities by identifying with Europe as a bulwark against their own past and ambitions of mighty neighbours. For them as for regions like Catalonia and Lombardy, which have long strained against the demands of a centralised Spanish and Italian state, being European and taking pride in local identity are complementary. Larger countries fear a loss of their special place, their distinct national image, through too close an identification with a Europe they cannot control.

But the most significant fault line today runs through countries, not between them. Whatever is distinctively European thought, taste, practices has always been restricted to a trans-national élite, united by the command of a common language, first Latin, later French, then English, and by a freedom of movement. It might surprise modern business executives, lecturers and politicians travelling from one European capital to another how much they have in common with the traders, theologians and emissaries who traversed the same routes centuries ago. Such cosmopolitan Europeans have always had more in common with one another than with their monolingual, less well-educated national compatriots. For this other Europe of farmers, workers and service employees, Europe is an abstraction. Thanks to television today even the poorest European citizens aspire to a certain common culture, but this is a universal, interchangeable, popular culture, not distinctly European, rather American. At a deeper level the less educated citizens of European states remain confined within narrow boundaries. Their concerns are local or national rather than continental and they are accordingly more susceptible to populist and nationalist appeals.

3. The Development of European Economic Integration

3.1 Building a European Economic Community2

The idea of pooling economic interests to overcome common problems was not a new one after 1945. The "United States of Europe" had been proposed in 1848 by the French newspaper Le Moniteur and there were various proposals made for an economic federation along Swiss cantonal lines. Another popular theme of the 19thcentury were customs unions, for example, proposals to extend the German Customs Union, established in 1834, to include the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark and even the Habsburg Empire, which failed. After the First World War the break-up of empires resulted in a disruption of production units and trade patterns, which made the need for cartels and trading pacts even more urgent. Wide-spread anti-Americanism and the fear of US competition continued to favour intra-European trade agreements, which were mostly bi-lateral, not multi-lateral as before 1918. One exception was the International Steel Cartel, founded in 1926, covering Germany, France, Belgium, Luxemburg and the Saarland, which was still separated from Germany under the terms of the Versailles Treaty. It was joined by Czechoslovakia, Austria and Hungary a year later, but renounced by German producers in 1929 and altogether abandoned two years later at the height of depression. Other similar efforts to boost the European economy in the interwar years was the Oslo Group of 1930, covering Scandinavia and the Benelux countries or the Fascist Rome Protocol of 1934 comprising Italy, Hungary and Austria. None of these attempts succeeded in preventing the collapse of trade in Europe. In 1938 Germany and France were still negotiating a trading agreement under which France would import more German chemical and engineering output in return for an increased German import of French agricultural produce. It was never to be ratified.

Diplomatic efforts accompanied these unsuccessful attempts at economic partnership. The German Gustav Stresemann argued in 1920 for an end to customs barriers and the creation of a Eurocurrency because he was of the opinion that Germany's own interests were best served by putting them into a broader European context. The Frenchman Aristide Briand developed plans for a "United Europe" in 1929. There were several precedents of a strife for a European unity to revive the economically depressed continent, from the Young Neutralists to the Pacifists and the Fascists, who spoke of a "renewed and re-juvenated Europe", united around their common set of goals. The Nazi Albert Speer's plans for a "New European Order" towards the end of World War II, rejecting the old liberal, democratic and divided pre-war Europe and propagating a German-dominated National Socialist union, led to the fact that the terminology of a "United Europe" was polluted immediately after World War II.

The creators of post-war European integration were driven by most conventional motives, realistic, national and traditional. They had grown up in a world of nation states and alliances. In 1945 the prospects of building any kind of European unity looked especially bleak. It is a mistake to believe that Europe was built by idealists because the idealists that existed had no discernable real-world impact. The British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and the Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden propagated a vague idea of a unified continent, but limited the idea of a "Council of Europe" to a meeting place and talking shop of Europe's leaders. The goals of most spokesmen for a united Europe were domestic. European statesmen were striving for reconstruction and reform in their home countries. Until the 1950s it was uncommon to find politicians or even intellectuals talking about a unified Europe. In fact, it was neither idealism that drove Europeans together, nor historical destiny, but economic need. After the Second World War it had become obvious that the Western European states had to cooperate economically to overcome post-war exhaustion. Those forms of economic cooperation, such as the Organisation of European Economic Cooperation (OEEC) or the European Payments Union (EPU), had no idealistic content and carried no implication of future European unity.

The time immediately after the end of World War II was dominated by the historical "French- German dilemma" and was not fundamentally different from 1918. The French had to resolve again their "German problem", namely how best to hold German power down to an unthreatening level while keeping it productive enough to ensure a sufficient flow of vital raw materials to restart the French industry. At that time France was uniquely dependent on German resources, especially coal. In order to fire its own steel plants France needed coal from the Ruhr and ironically, the return of Alsace-Lorraine after 1919 had increased this dependence, as it doubled French steel-making capacity without adding significantly to its coal supplies. So France's strategy was an urgent exploitation of German resources and at the same time a reduction of German political and military power to the minimum. It would have been a replay of the unsuccessful strategy that led in 1923 to the French occupation of the Ruhr. But this French policy was incompatible with the British and American policies which wanted to revive the Western German economy. They planned to boost the West German economy, firstly, for the sake of European economic recovery and secondly, to relieve the British of the cost of feeding and housing the people in their zone of occupation. Finally, especially the Americans wanted an economically strong Germany as a partner against the Soviet Union, at a time when tensions were already rising and the onset of the Cold War was imminent. The US military commander in Berlin, General Lucius Clay was about to accord to Western Germany a certain degree of autonomy to help the economy recover. The French leaders tried to work around this British-American strategy by allying with the Soviets, a replay of traditional French diplomacy of associating with a strong partner east of Germany. Initially, the Soviets had no objection to the French exploiting German resources, when they themselves were dismantling German assets in their zones of occupation and exploiting German raw materials to the full, especially as it antagonised British and American interests. But with the onset of the Cold War the Soviets had no use for French diplomatic manoeuvring and rejected the French plans. So France had to adopt a third strategy, namely accepting the need of a revival of the Western German economy and a unified Western German state while hedging it around with international alliances and economic agreements and by that ensuring the French access to German resources.

Vital for the Jean Monet Plan was the French industrial reconstruction that depended on the availability and affordability of German raw materials. Yet the original plan was too limited, reproducing the trade-restricting tariff agreements of the interwar years and negotiations failed. That's where the plan of the French Foreign Minister, Robert Schuman, for a six-nation community to share and regulate the production and consumption of coal and steel under an autonomous international authority came in. This proposal took the imaginative leap from the Monet Plan to a new concept of accepting the participation of Western Germany and the absence of Great Britain. In 1950 the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), the kernel of the European Union, was the second best solution. The British thought they could still stay outside a European cooperation, secure in their political and economic links with the Commonwealth. They lacked the wartime experience of occupation that led other European countries to accept an economic cooperation that included Western Germany in return for a peaceful economic development and a national revival. For decades the British thought they could go on as before the two World Wars, which was a grave misconception and resulted in smaller growth rates compared to other European countries in the 1950s and 60s. The French accepted a European solution to their German dilemma only after their preferred strategies had failed. Nevertheless they were successful beyond their expectations in "Europeanising" their historical problem by incorporating Western Germany into an originally French-dominated community. France was given the chance to take initiative and the absence of Britain was felt as a kind of "sweet revenge" after decades of diplomatic humiliation by the British.

Western Germany, of course, would have preferred a broader economic union, just like all the other partners except France, but they agreed to the ECSC on French terms as a first step back into the international community of states and to gain French support for their primary goal of increased sovereignty. The Netherlands and Belgium feared a US retreat from Europe and a repetition of American isolationism of the interwar years. So they attempted to keep at least Britain engaged in continental Europe but failed. They agreed to a much reduced community because they needed to see the German economy restored in order to revive and modernise their own industries and to be able to sell to a growing German market. In that way Germany constituted a counterweight to the French economic domination in that area.

The result of this political process was an emerging European unity that was in certain aspects an accidental construction und still unpredictable in form, content and membership. In those days no one was talking about giving up sovereignty or a political union. The ECSC, signed in 1951, did not yet signify a peaceful and economically strong Europe; it was rather a kind of "peace treaty" between Germany and France by institutionalising their important mutual economic dependence. Once the European Recovery Programme, better known as the Marshall Plan, phased out in 1952, the limits of the Schuman Plan became evident, but France blocked any attempt at further European integration, such as the "Green Pool", proposed by the Netherlands to coordinate agricultural output or the "European Defence Force". The economic boom of the Miracle Years raised the need to stabilise trade in more than just coal and steel, so initiative was recovered in 1955 at a meeting in Messina, Sicily. The high rates of economic expansion forced upon Europe some sort of regulation. So the 1957 Treaty of Rome agreement to establish a Common Market, The European Economic Community (EEC), was the result of new economic developments the six members had to channel and contain, just like its predecessor, the ECSC. They had to develop new devices to tackle occurring economic problems, such as agricultural production.

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) constituted and still constitutes a gross misapplication of resources. For a long time it has been the most expensive European economic policy by keeping European agricultural target prices above world level while guaranteeing to buy surpluses at predetermined rates. In the 1970s it took up 70 per cent of the EEC budget. Why then had the other five members given in to French pressure in 1957 to implement CAP?

Firstly, one answer to this question is historical. Since the late 19thcentury Europe had suffered from rural overpopulation despite urbanisation and emigration. The majority of peasants barely scraped by and after World War I the situation worsened, when the prices for agricultural products decreased rapidly. The democratic governments of the interwar years could not do anything to raise agricultural prices because higher food prices would have worsened the situation of the urban population that was already suffering from deprivation and unemployment. Furthermore no investments were made in agricultural support programmes due to strict laissez-faire economic policies. The high rates of urban unemployment excluded any alternative occupation of the peasants in the cities. Authoritarian regimes, on the contrary, imposed policies to ensure agricultural autarky. So a desperate peasantry turned to fascist and populist parties everywhere in the interwar years. The fact that Europe's depressed farmers had proved so susceptible to the Fascist appeal turned out to be a major element in the willingness to agree to CAP in order to win the European farmers over to democracy.

Secondly, in the 1950s farmers were still a significant presence in Europe; in France they constituted 30 per cent of the labour force and in Italy even 43 per cent. Thirdly, immediately after the Second World War, Europe suffered a chronic food shortage, and there was an urgent need to produce as much as possible to reduce imports from the dollar zone to save precious foreign currency. Consequently, farmers were encouraged to produce as much as possible as fast as possible with the help of wartime aid measures, which were kept in place. Reforms were passed in France and Italy to confirm and improve the rights of tenant farmers and farm labourers in the hope to convince them of the benefits of democratic policies. But once the immediate post-war agricultural production crisis had been overcome the Europeans had to cope with a new situation, namely how to keep food prices high for the farmers and at the same time at a reasonable level for the consumers. With the economic boom in industrial production and trade of the Miracle Years the welfare gap between urban and rural workers had started to widen again. At that time the supply of food was already growing fast despite a rapid and continuous fall in the labour force engaged in agriculture.

The result of trying to tackle these problems was CAP. The French government only accepted trans-national aspects of the EEC in exchange for a protection of their agriculture from competition, especially from Denmark, and the Netherlands went along with France. For Western Germany CAP represented an economic advantage in the south only, but for Western Germany it was the price that had to be paid for an expanding trading community. Only in return for CAP would France adopt common commercial policies and an "ever closer union", as mentioned in the Preamble of the Treaty of Rome. In effect, CAP never benefited a majority of peasants, even in France because it was and still is mostly advantageous for big grain and dairy producers and offers much less to small farmers of olives, wine, fruit and vegetables. The true function of CAP therefore is political and not economic. While farmers have become decreasingly relevant in electoral terms, constituting below ten per cent in Western Europe, and because the traditional rural society has been swiftly melting away, a compensatory myth of its cultural centrality, not only in France, grew and a powerful belief has spread that rural communities and rural culture have to be preserved and protected. This guaranteed the survival of a very costly European agricultural protection programme until today, in utter contrast to the general drive of European economic policies and out of all proportion to the size of the European constituency.

In this way CAP illustrates the whole enterprise of European integration. It has always been an outcome of separate electoral concerns, economic interests and national political cultures, it was made necessary by economic and political circumstances and it was made possible by the prosperity of the economic Miracle Years. The achievement of this integration process was an astonishing and fast economic recovery and the resulting wealth and prosperity of Western Europe. By avoiding the disasters of two World Wars and the Great Depression its success is singular in European history as a peace project and an economic programme. Three aspects rendered this success possible: First, the impact of the war itself. Europe with the exception of Britain had become defeatist and wary of any commitment to war. Past emphasis on national and military achievements seemed inappropriate and the attention was turned to social and economic affairs. Second, the Cold War: It forced Europe into a greater measure of unity and collaboration while sparing Europeans high military expenses, which were taken over by the Americans. A re-armament after the war would have been economically and politically disastrous. Finally, the disastrous economic history of the inter-war years led to a drastic change in social and economic policies along Keynesian lines, which resulted in a long and unprecedented era of relative social peace and economic and political stability. For the economic take-off mainly three factors were responsible, namely first, the American aid and the willingness of the American administration to spend it on a programme for European economic recovery, second, the acute labour shortage until the 1960s that provided labour for the people from the economically depressed areas of Western Europe and then for cheap foreign workers and third, coal. Without the vital interest that coal had played and was expected to play in the future, the Western European states might not have had a shared interest in an economic community. For the six founding members coal and steel was a domestic problem that drove European integration forward.

But more than US dollars, docile and cheap labour and coal, it was luck that contributed to the unification process. Five of the six founding members were among Europe's potentially wealthiest and economically most efficient states, the community could wait until 1973 to incorporate three more members, two of which wealthy again, Britain and Denmark and before 1989 the community never had to worry about absorbing the really poor nations in Eastern Europe. All this made this European trade partnership different from all the previous attempts, and on top of that its expansionist future intentions. From the beginning the community claimed that its interests would be best served by extending to others their rules and benefits.

3.2 Problems of European Integration3

As we have seen in chapter 3.1., the movement that has actually produced the existing European Union was not based on strength and potential, but on the exact opposite, weakness. After World War II the need to avoid suicidal wars of mutual destruction became evident, at least to Western German and French governments, and coordination between those two states formed and still forms the cornerstone of Brussels politics. Weakened as single states, former "great powers" could now count only as part of a coordinated Europe. Britain, which after 1945 still hoped to maintain itself as a global power and global empire, finally abandoned this hope after the collapse of its empire.

Four problems derive from this origin of the European Union:

First, this pragmatic development of the community would probably not have taken place but for the Cold War, the combination of fear of one superpower and strong pressures from the other, notably the pressure to integrate Western Germany into the anti-Soviet front. The community grew up as a part of the American anti-Soviet block, though formally outside the military system NATO. With the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union it lost the stability of bipolar confrontation and was faced with problems it was not prepared for as part of the American alliance. The two most obvious were and still are, how and how far to extend the EU to formerly communist European countries and how to acquire a common foreign and military policy after emerging from under the umbrella of US Cold War policy.

The second problem derives from the nature of the construction of the EU, developed from the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951. Considering that electoral democracy was an essential qualification for membership, its absence from the institutions of the EC is striking. The EC was constructed from the top down, outside the scope of the democratic politics of its member states. The machinery of the EC made no real provision for an all-European democratic element, although it took over from the ECSC a consultative assembly, renamed the European Parliament in 1958. Some slow and reluctant concessions to the public rhetoric of democracy and the pressure of the European Parliament have been made, especially since 1979. It might be misleading to speak of a "democratic deficit" of the EU, as it was explicitly constructed on a non-electoral basis and few will seriously argue that it would have got where it is today and would have achieved what it has otherwise. It may be transformed into a directly elected democratic entity, but if it is, its character will be profoundly changed. However, one must add that for its first decades, the EU benefited enormously from the fact that neither voters nor politicians in the member states took much interest in its affairs, knew much about them, or - except special-interest groups like businessmen and farmers - saw them as of more than marginal importance for themselves. Generally speaking, the citizens of member states regarded the community as concerned with technical matters like tariffs and as broadly beneficial, with relatively minor and manageable drawbacks. Since the Single European Act (SEA) of 1986, this has changed. "Europe" has become a major issue in the national politics of the member states and has sharply divided their politicians and electorates. Moreover, as the EU has moved closer to political integration since the mid-1980s, the feebleness of its democratic component has become increasingly evident and ideologically embarrassing.

Third, the EU was built by a marriage between, on the one hand, national governments that for one reason or another thought of a union as helpful to the interests of their nation states and, on the other hand, a pressure group of ideological missionaries who believed in and worked towards the building of a single federal or confederal Europe. In the SEA this conflict between the two concepts of Europe became evident. The conflict was highlighted as on some issues the SEA substituted majority voting for unanimity and by that, depriving member states of their automatic veto on community decisions. After the end of the economic Miracle Years it became clear that the European Economic Community could no longer rely on the socio-economic consensus that had underpinned it, the combination of market and welfare and the partnership of state, capital and organised labour. The rise of free-market neo-liberalism undermined the Community's cohesion as much as the collapse of communism. In ultra-liberal theory, even a large trading block like Europe arming itself against rival economic blocks, such as the USA and Japan, was an unacceptable interference with free enterprise in the global economy. The problem nowadays is that only the European Union and the economists and politicians responsible for the current EU economic policies seem to see it this way, while all the other economic blocks are already protecting their economic interests in very intricate ways. Politically, the Community was then under attack from two sides, from those who disliked its encroachment on the national state and from the champions of a single free-trading world economy against trading blocks. Unfortunately, the ideologists' project of building Europe based on a European identity had never had a real political constituency in the member states. Changes in the world economy now may require reinterpretations of the "4 freedoms" of the EU that are its basic principles: freedom of movement of goods, persons, services and capital, since the EU's function today is increasingly supposed to be that of strengthening and protecting the global economic competitiveness of a regional block against other economic blocks, as well as preventing the freedom of movement of persons from outside into Europe.

The fourth problem of integration poses the historical heterogeneity of the continent itself. The "European project" tried to minimise this problem by making common political and economic institutions a condition of membership and by avoiding too great a disparity between the economic and social levels of the members. That's why the application of Turkey has been postponed for so long and is still hotly discussed. With the accession of notably poorer and more backward economies like first Greece and Portugal and then Bulgaria and Romania, the scale of the problem was underlined. The solution was transferring income from richer to poorer areas through structural funds. Even if we suppose that the economies, political systems and living standards of Europe's countries and regions converge more rapidly within the EU, Europe remains heterogeneous and is and should be proud of it, not just because of the many languages spoken within the EU. Almost one quarter of the administrative staff of the EU consists of translators and interpreters, making it the world's largest linguistic service. Though the EU exists to facilitate freedoms of movement within its borders, the surprisingly low rate of population shifts within it, compared to the USA, indicates the reality and importance of these cultural barriers, and the immobility of the European population.

Yet the decades of impressive evolution of the EU until the late 1980s took place out of sight of mass public opinion. Essentially, the considerable advances in European integration rested on two pillars then, the powers of the European Commission and the European Court of Justice. This period of comparatively unproblematic advance ended in the 1990s. The increasing politicisation of Europe has dramatically reduced the Commission's ability to pursue its objectives untroubled by member governments' politics, but few other effective initiators of policies has appeared so far. However, there is still room for the traditional Brussels-initiated process of "Europe-building" to continue in those areas that have not yet been politicised, at least until they are. For instance, the Union's redistributive function, especially its regional policy, has grown rapidly. A majority of countries have benefited by this redistribution, even in countries that paid more into the EU's budget than they received back, poor and backward regions benefited from EU subsidies. Also this development, which has introduced a special recognition of regions and a direct link between those regions and Brussels, bypassing their national governments, has political implications. These have already been recognised by separatist movements in for instance Spain, Britain and Italy.

The power of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) rests on the fact that member states have given EU law precedence over their national law and that there is no appeal to any superior court. Its judgements inevitably affect the constitutional law of the member states and imply a significant diminution of their sovereignty. The ECJ was originally set up to settle problems of the interpretation of the treaties establishing the EEC, but its importance has grown substantially. Most of its decisions take the form of a preliminary ruling on a case referred to it by a national court when a point of European law is at issue, with its ruling then being applied by the national court. Only the belief that the EEC was primarily concerned with technical rather than political matters, and the lack of massive public interest in its affairs, can explain why so major an abdication of national sovereignty was allowed to pass into the member states' legislation so easily and without public attention. Yet, once accepted, the supremacy of the European law cannot be ended. So at present and in the foreseeable future, the standardisation of national laws through the decisions of the ECJ constitutes the most powerful and permanent element in European integration. The judgements of the ECJ both shape, reflect and set the balance between European and national law.

4. European Cultural Convergence4

Despite the persistence of a strong and lively cultural diversity across Europe, a certain convergence of national and regional lifestyles can be seen throughout Western Europe since 1945. It is based on the spread of a common staple of consumer goods and leisure activities and rising and converging living standards. The household expenditure on basic needs, such as food, housing and clothing steadily declined since 1945. After the Second World War this expenditure constituted half or even more than half of the average household budget; in France e.g. 65 per cent. By the 1990s the household expenditure on basic needs had fallen to an average of one quarter in most countries of Western Europe, while in the 21st century the share has been rising again, especially in less well-to-do households, as the welfare gap is significantly widening again. The reduction in basic expenditure allowed an increase in demand for consumer goods and services. Yet it is interesting to see that especially in the area of basic expenditure regional tastes and customs proved most resilient. In housing North Western Europe's pattern of smaller houses contrasted, with the exception of large blocks of council house flats in Britain, with tenement houses and high-rise apartment blocks in the Mediterranean region. This trend was reinforced by new building projects up till the 1980s. Traditional eating habits persisted as well. The most visible European trend was the diffusion of American style fast food since the 1960s and not any kind of European food tradition. In North Western Europe a spread of oriental food was triggered by immigrants who were prepared to toil in small, often take-away, restaurants for very low wages. Popular lifestyles in Europe were approaching American standards and in this, as in many other respects, an apparent "Europeanization" was more of a much broader "Americanisation" on a world scale. Just like several other idealist European goals, the European mass culture turned out to be something else, namely more of an American mass culture.

Since the last decade of the 20thcentury the cultural landscape, as well as the social and political one, has changed considerably in Europe. People change their domicile and country more easily, they have continuous access to information on a planetary scale, and they have formerly unknown powers of consumption. This transformation has occurred within one generation, whereby children were generally more educated, cultivated and prosperous than their parents. The main reason for this change in lifestyle was the enormous increase in educational standards, from literacy levels to secondary and university education. For the first time in history more or less the whole population of Europe was literate and a very high percentage had a university education, some European countries, such as Britain, are planning for half the youth population to go to university in the next decades, more than a third are already doing so.

Non-material belief systems, such as religious practices and regional folk customs, lost importance or disappeared altogether, but some have been revived for tourist purposes. The urbanisation process is one of the main reasons for this trend. Even in remote areas, old beliefs and practices waned or were converted into tourist attractions. The commercialisation of everything also reached European traditional culture and customs. Everything now had its price and was turned into a product that had to be attractively marketed. "Traditional Europe" was turned into a kind of television show for holiday makers. Tradition thus merged into the consumer society, backed by the mass media. Advertising was the most apparent means of directing behaviour across Europe, while the news and entertainment content of the media had an indirect impact, wrapped up in the commercials. The main linguistic medium of this convergence, also in Europe, was English. English achieved a growing importance after the war as the main commercial language owing mainly to its use by the Americans. The emergence of the internet then further boosted the use of English as a means of communication in Europe. English culture also made a contribution, as its European character rendered it in some ways more acceptable to Europeans than American culture. But over the following decades the mass culture of Western Europe was increasingly converging, no matter in what language it was expressed. One example would be the television shows with exactly the same concept, content and setting that are produced in all the main languages of Europe for the national audiences.

There has always been a tendency for elites from each European nation to share a world or global culture. But today we are faced with something quite new: a process of getting cultures to conform on a planetary scale, the global spread of mass popular culture. 90 per cent of films seen in the world, with the exception of India and Japan, are American productions. The same is true for music, the MTV generation listens to the same music world-wide and famous football teams only employ a handful of native players. Technological inventions, especially in the field of communications technology and the economic aspect of the global market have enhanced this global mass culture. There is however a difference between traditional 19th century high culture and modern mass culture. Traditional high culture spread via a European cultural model that has been adopted globally and was globalised in this way. A classical concert programme in Osaka, Chicago and Johannesburg presents the same kind of repertoire, i.e. European classical music. This is not true to the same degree of literature because of a very powerful limitation on globalisation, namely, language difference. Even literary classics and bestsellers have never been globalised in the way music and the visual arts are. In popular culture, on the other hand, we are faced with widespread syncretism at the beginning of the 21st century. The most obvious example is popular music and its assimilation of various elements, such as Afro-American, African, Latin American and white country and western elements. A combination of all different musical traditions is travelling around the world. Global popular culture is the product of the readiness to mix different elements coming from different parts of the world. High culture does not share this propelling force to the same degree yet. Popular culture is shared by everyone somehow, including those who are familiar with high culture, but the opposite is not true.

Yet in spite of the spread of mass global culture, there is clearly resistance and even a revival of local, regional and national cultures in Europe. The Welsh discover Welsh, the Bretons Breton, Pakistani girls in London dress traditionally. It seems that globalisation itself cultivates diversity and cultural differences as market opportunities which, although directed at niche markets, are profitable nevertheless. Furthermore multilingualism, by definition, is an obstacle to globalisation. The idea that one day all Europeans will speak English only and all other European languages will become extinct is utopian. One aspect must not be confused: globalisation, which is a real and wide-spread phenomenon, is quite different from cosmopolitanism, which is still extremely limited. Obviously, the clashes between dependence on tradition and individual autonomy on the one hand and between fundamentalism and cosmopolitanism on the other hand characterise the present globalisation process. The foundations of European societies and societies world-wide have been disrupted by the economic, social and cultural revolutions of the late 20thcentury. Anything like this break with traditional lifestyles, anything that upsets tradition has some effect on fundamentalism, and globalisation is obviously one of these triggers. Many of the traditional bonds that tied an individual to his/her reality have been weakened, such as loyalty to the family, village, neighbourhood and company; insecurities in bondage, relationships, in employment have increased. With the erosion of traditional societies, religions and beliefs and the snapping of links between generations, the values of the absolute a-social individualism have been dominating Western European capitalist societies. The capitalist economy fosters a society of otherwise unconnected self-centred individuals pursuing only their own gratification. Yet, the triumph of material progress based on science and technology has triggered exactly the opposite, namely a rejection of these attitudes by a large part of the European public. Calls for the "community", the small regional unit have become louder. The problem very often is that many people see no other way to define identity except by defining outsiders, who are not in the group. The growing economic disparities and the dissolution of traditional social norms and values, leave many people bereft and at a loss and make them easy targets for anti-foreigner and anti-European populist appeals.

5. The Challenge of a Common European Social Policy5

By the time of the treaty of Nice in 2001 the EU had acquired considerable responsibility in the social field concerning the issues of employment, industrial health, industrial social costs, labour mobility and the role of social spending in social affairs. A more integrated approach to social issues, combining employment, social protection and economic and budgetary policy might be envisaged. In the early years of the Union, broader issues of social welfare were of little relevance, but the EU's social competences have grown since. There are several reasons for this. First, social affairs form a large component of national policy and have to be fitted into the European framework in the course of the integration process because more problems have a trans-national element nowadays. Second, Union policies have been reaching more into detailed areas of life over the years, such as equal opportunities policy. Especially during the 1980s the Commission, backed by the European Parliament, felt it was supposed to play an active and positive role in social affairs and stepped up the social momentum to strengthen the legitimacy of the Union. The Commission has often clashed with national governments, which still wish to claim credit with their citizens for their work to improve the conditions of life, notably over the "social dimension" of the single market. The argument from Brussels has always been that the Union has to come closer to its citizens, a view that encourages an ever more important social role. Social policy in the EU now covers several individual policies, and five Commissioners and their directorates have direct responsibilities for the items under the umbrella of social policies. Some provisions in treaties are clear-cut, but many are of a very general nature and do not require legislation but political programmes. That results in a wide variety of activities that demand a different degree of commitment from the member states. A consequence of this is the growing overlap of interest with that of national authorities which leads to cooperation, but also to conflict. National governments remain primarily in charge of education, health care, social security and housing, which are overwhelmingly financed from national sources. Community interest is often marginal to the main body of work carried out nationally since the EU is primarily driven by economic objectives and the current emphasis on subsidiarity cements this division. In education for example the EU accepts that the member states are mainly responsible for fulfilling their educational needs, but stresses the European dimension by supporting language programmes, staff and student mobility and cooperation between different member states' educational institutions. Political and human rights have been covered extensively in several treaties.

The 1990s were years of relative stagnation in European social matters, but the year 2000 marked a new beginning. The new optimistic strategic aim for the next decade was to become the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world, capable of sustaining economic growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion. This strategy should be implemented by improving the existing processes and by stepping up integration of social domains so far separated, such as employment and social protection, and of economic and social policies. The ultimate goal was to modernise the European social model by investing in people and combating social exclusion.

The table below shows the distribution of income or consumption in EU countries around 2000 in comparison with the United States, Russia and some other comparators. Most interesting is the Gini index, which is the Gini coefficient expressed as a percentage. This is a measure of inequality of income or wealth distribution. The lower the percentage, the more equal the wealth distribution in the country. The table shows that all 27 EU member states show a percentage far below the United States and Russia, which means that wealth is distributed much more equally in Europe. The European countries with the most equal distribution of income are Denmark (24.7), Sweden (25.0) and Finland (26.9) from the "old" EU countries, Slovakia (25.8), Hungary (26.9) and the Czech Republic (25.4) from the "new" EU countries, this of course on a lower per capita income level than the "old" EU countries. The countries with the biggest welfare gap in Europe are the Baltic States (between 35.8. and 37.7) in the "new" EU member states and Portugal (38.5), Italy (36.0) and Great Britain (36.0) in the "old". In Europe Austria (29.1) lies somewhere in the middle. These European figures have to be compared with Russia (39.9) and the USA (40.8).

Figure 1: Income distribution. (Source: El-Agra, Ali, ed., The European Union. Economics and Policies, CUP 2007, p. 103)

5.1 Industrial Relations in the EU

The social dimension of the EU depends among other things on whether labour unions succeed in mounting solidaristic action in defence of Europe-wide labour standards and social policies. Without a strategy of internationalisation, national labour unions are caught in the downward spiral of desperately defending their declining domestic power base, and they are in danger of falling for protectionism in defence against trends beyond their control. Since the 1980s the intensity of global economic competition, persistent high unemployment, the ascendancy of neo-liberalism, new forms of employment outside traditional contracts of employment, and new steps toward European integration have tended to undermine the effectiveness of organised labour at the national level. From a European perspective, globalisation refers to three interrelated processes, the rise of trans-national corporations, the partial loss of economic and political autonomy and of the sovereignty of national states and the global shift in economic power from Europe and North America to Pacific Asia and low-wage economies in general.

The rise of the trans-national corporations and the globalisation of the economy have changed the balance of power between firms, states, and unions. On top of that, labour's interests and objectives vary considerably across Europe due to substantial differences in the prosperity of Europe's national economies. Poorer countries tend to perceive Europe-wide labour standards as devices to protect richer countries against the transfer of investments and jobs towards the weaker economies. High labour standards thus draw only half-hearted support and are often undermined, especially when common social minimal standards are not backed up by a redistributive policy of the richer countries, paying more in order to enhance the productivity of the weaker economies and poorer regions.

The main economic rationale of European integration has always been to enhance factor mobility and efficiency rather than to promote redistribution and equity. Initially, it was assumed that increased economic interdependence would produce the convergence of economic factors. Yet, when no such tendency was observable, European politicians abandoned the harmonisation target in favour of the principles of "mutual recognition" of national producer standards, a qualified majority on EU deregulation measures, and subsidiarity in matters of social policy regulation. Despite the EU cohesion measures assisting weaker economic regions, the EU is not a redistributive welfare state guaranteeing social rights against the vagaries of the free market. Labour market institutions and social security arrangements in Europe still have a high national content, in spite of today's deregulated market forces and decades of European integration. The influence of unions over social and economic policies is typically confined within, and dependent upon, the national welfare states and, hence, different from one country to the next.

Barriers that stand in the way of trans-national union co-operation in Europe are first internal barriers. Europe is a continent not only of peoples with different histories and languages, but also persistently diverse industrial relations. European labour unity poses the same problem as political union: how to encompass and manage national diversity. The sources of union diversity are rooted in the national histories of labour movements in Europe. The particular form of party-union relations within the labour movements varies widely across countries. This "nationalisation" of organised labour has deep and lasting roots far beyond national interests, values and symbols. Since nationally distinct patterns of representation and collective action are strongly institutionalised, these are obstacles to a common European social policy. The current downward trend in unionisation, the financial crisis of labour movements, and the unions' dependence on state or party support do not make the problem easier. As national labour unions come under pressure to spend their meagre resources on visible membership services, European-wide activities are hardly likely to receive priority. Across Europe, union movements maintain different linkages to the political system. In the past, union movements drew strength from their partisan linkages, especially when the allied party was holding government office. This partisan involvement has caused deep divisions within and large variations across European countries.

Cross-national diversity in industrial relations is also huge with respect to employer associations, collective bargaining, state regulation, and institutionalised forms of worker participation. Despite the expectations of convergence theory, different political, legal and cultural contexts bear heavily on industrial relations in each country. Moreover, the Brussels power play does not appeal equally to each national union movement; its appeal depends largely on national contingencies. Some union movements have reason to fear the loss of their "quasi-public" status at home; others hold so little status in the domestic public arena that they can only gain from going to Brussels.

When organised labour engages in EU lobbying, it encounters a complex set of supranational and intergovernmental institutions with restricted regulatory competencies, underdeveloped executive powers and a multiplicity of actors. Many of the most important industrial relations issues are explicitly excluded by the EU treaties from supranational policy making, including the main rules of the game for collective bargaining, strike action, and worker representation. European supranational institutions, however, constitute a number of points of access for lobbying, in particular the European Commission, the European Parliament (EP), the Economic and Social Committee (ECOSOC) and also regional committees. Yet the powerful and remote governmental committees; the European Council, the Council of Ministers, and COREPER (Comité des Représentants Permanents), composed of representatives from EU member states, elude labour unions and can be reached, if at all, only through national channels.

Yet the rulings of the European Court of Justice have tended to expand the scope of initially restricted social regulations under the EU treaties. The role of the EP has increased and now influences much more of EU legislation, but its powers are still limited compared to national parliaments. The Social Protocol requires the co-operation of the EP in several labour and social policy areas, but in these domains, the position of the Council of Ministers and hence national governments remain strong. Yet the extension of qualified majority voting and the signing of the Social Protocol should have improved the chances for a common social policy, but not much has been achieved for the European employees so far.