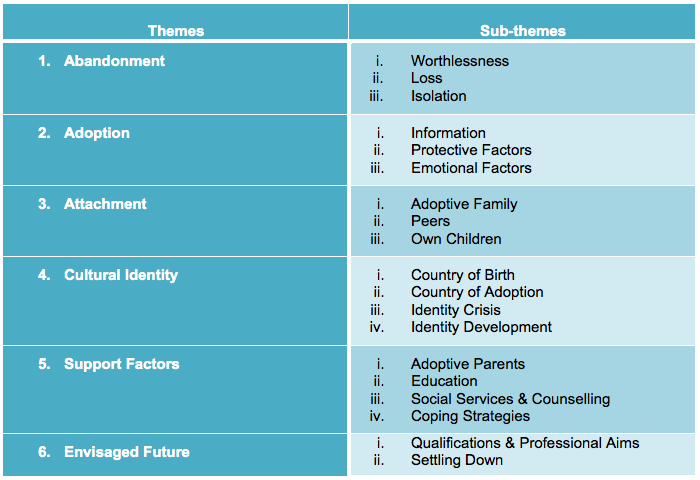

Table 1: Themes and Sub-themes of Interviews

soziales_kapital

wissenschaftliches journal österreichischer fachhochschul-studiengänge soziale arbeit

Nr. 8 (2012) / Rubrik "Nachbarschaft" / Standortredaktion Wien

Printversion: http://www.soziales-kapital.at/index.php/sozialeskapital/article/viewFile/239/378.pdf

Elizabeth Baum-Breuer:

1. Introduction

Nineteen young people with exposed life histories: This paper explores the implications of transnational adoption for the life path and identity development of individuals who were abandoned or placed for adoption at a very young age in far away countries and continents. The study deals with a global theme and touches on the cultural background of thirteen different countries, from Bolivia to Sweden, China to England, India to Austria. In addition, the paper traces the historical development of transnational adoption and sketches a profile on functions and expectations of families and children in the Western world against the background of different welfare systems (Esping-Andersen 1990). A comparison of the three very different adoption scenarios in Austria, England and Sweden reveals controversial considerations, while a further theoretical focus pertains to biography and identity theories relevant for adoptees. This study offers a direct and explorative contribution to research on adoption within a life-span and pedagogical context, employing a phenomenological approach and a triangulation of qualitative methods, an Interpretation of Pictures and Documentary Method (Bohnsack 2008) in combination with a Thematic Content Analysis (Merten 1995, Smith/Harre/Van Langenhove 1995).

Children of foreign nationality placed for adoption in a new home country are very special members of the societies in which they live. In part, they also signal the ever-increasing trends towards globalisation. The search for identity is the narrative for many people’s adult lives, especially for many transnationally adopted persons. Their search for family (which often brings no concrete facts) is often coupled with the quest for racial and cultural identity. Many uncertainties pave these children’s paths through adolescence into adulthood.

Adoption is essentially a social and legal protective measure for children and should always be conducted in the interest of the child. Only where the birth family does not meet conditions that ensure the child’s psychosocial, physical and emotional development should alternatives (including adoption) be sought. Due to a lack of children free for adoption in affluent countries of the West, transnational adoption has become a growing phenomenon (also in Austria) with around 45.000 children currently moving between some 100 countries per year (Selman 2009: 575-594). At its onset in the aftermath of World War II, international adoption was mainly a philanthropic response to devastating natural and manmade catastrophes. However, in recent years thousands of young subjects have encountered great dangers in the realm of child trafficking.

Regardless of what supporters or critics say in this controversial debate, transnational adoption is a reality of today’s globalised world. The issue being subjected to ever increasing scrutiny and debate by theorists convinced that the process of incorporating the growing diversity of migrants into contemporary societies necessitates a fundamental re-thinking of crucial concepts like culture, ethnicity, community and identity (Bhabha 1994, Maalouf 1998). Transnational adoptees have identities which are impacted by two cultures and their growing up entails a transcending of geographical and cultural borders.

Therefore this study sought to learn if - and how - transnational adoptees have been impacted on by new post-modern hybrid forms of identity developing among the young generation (Hugger 2007: 173-184). "Hybrid Identity" (Hein 2006) may on the one hand pose a conflict of culture for individuals, on the other hand it can open up the possibility for access to multiple cultures, by means of "cultural navigation" affording individuals of bi- or multiple cultural heritage with active coping strategies. Adoption can be a great chance in life, however it can also pose a great risk, for if this bridging of cultures cannot be accommodated, there is danger of a life-long tear between two cultures.

2. Research Enquiry

The focal research question of this study is: "What are the implications of transnational adoption for the life trajectories and the identity development of individuals?" addressing five research enquiries:

Biography research is interdisciplinary, being represented in various disciplines and schools of human sciences. Life histories and autobiographies are central to modern pedagogical thinking (Krüger/Marotzki 2006), and are a basis for empirical data. By following the course of identity development as a dynamic learning process throughout the life span, this study underlines the role of education and the value of intergenerational transfer, thus positioning it within a pedagogical context.

3. Methodological Approach

The methodological approach is qualitative employing an Interpretation of Pictures Approach and Documentary Method in combination with an Interpretive Thematic Content Analysis applied to semi-structured Problem-centred interviews. The interviews set out to explore how transnational adoptees adapt to their new lives, throughout various developmental transitions in their adoptive environment. These interviews required that each subject answer eighteen questions pertaining to their life experiences while a further four questions centred on personal photographs which participants had been requested to select for the study.

4. Interview Analysis

The thematic content analyses on the transcripts of these interviews revealed six themes and nineteen sub-themes.

Table 1: Themes and Sub-themes of Interviews

Poetry and prose written by transnational adoptees raised and residing in England were employed to introduce each theme and sub-theme and to illustrate and accentuate the explicit data, obtained from the interviews (a representative example of poetry is included later in this paper, introducing a short summary of results).

5. Photo Typologies

One of the main aims in choosing the medium of pictures for this analysis was to approach the subject of identity development in a re-constructive way, proceeding from the immanent literal meanings of the respective photos to their documentary meaning. The interpretation of the choice and content of the carefully selected and analysed personal photographs revealed three typologies: people, places and possessions.

Figure 1: An example of a photo submission from a twenty-one year old female student in the typology ‘possessions’: These shoes were purchased by the adoptive mother in Vienna before leaving for Romania to collect her daughter who wore them when she travelled to her new home country Austria. The adoptee has kept these shoes which have high symbolic value and epitomise for her the adoption experience, comforting her during the on-going difficult search for balance and grounding in her young life.

The intention in applying the Documentary Method was to gain a methodical access to pictures, treating them as self-contained, autonomous domains and subjecting them to analysis in their own terms, allowing verbal contextual and pre-knowledge to be methodically controlled in the documentary interpretation of pictures. This acknowledges that pictures have a methodological status of self-referential systems and are a source of orientation for everyday practice on the quite elementary levels of understanding, learning, socialization and human development.

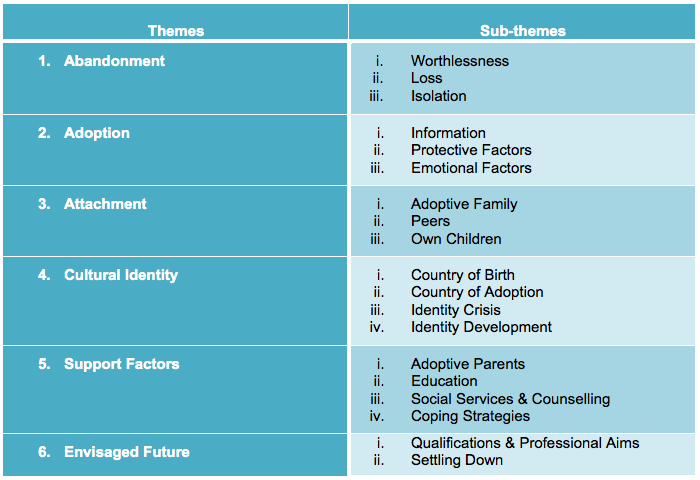

A further example from the photo collection and the largest typology (people) gives an indication of the importance of pictures and images for practical action and orientation for these actions.

Figure 2: This group photo was submitted by a twenty-four year old male farmer adopted from Sri Lanka to Central Sweden. It shows his birth mother and birth brother and adoptive mother at the occasion of his adoption. The picture forms the centre-piece of a family collage that hangs above the bed of his adoptive parents in Sweden. The adoptee’s "Brown Mama" as he formulates is a very central part in the life of his "white mama and white papa" as the positioning of this picture proves.

In this example, there is a marked influence on the level of behaviour in social situations. Someone (either the birth mother or adoptive parents or perhaps a social worker) ensured that a photo was taken of the adoptive child with his birth family members in order to give him a link to his heritage. This photo then proved to be exceedingly important when the subject of identity development became relevant for his own life-course.

6. Summary of Results

"I remember being abandoned.

It is etched deep inside my body.

It is a wholly sensory memory.

[...] It is a pre-verbal memory.

I told no one about it.

I had no words,

so I could not tell anyone about it.

Imagine that!

I imagine it as a black hole." (Weymont, 2006:20)

Three major trends pertaining directly towards the main research question and five research enquiries emerged: these trends were Protective Factors; Social Networks and Time Factor (regarding interest in adoption related issues such as biological origin, country and culture of birth).

This summary outlines the broader spectrum of these three considerations. Arising out of the respondents’ answers was the pain of coming to terms with abandonment, regardless of whether this was in the literal sense of being abandoned, of having been given away or of not having been wanted enough to be kept. It was notable that the younger the respondents, the less they had dwelt on this issue, being still more cocooned in their adoptive family environment. It appeared that the more settled and confident adoptees were in themselves, the more they could afford to consciously delve into the depths of their background and origin.

In order to enable adoptees to gain self-confidence and trust after the drama and trauma of their introduction to life, ‘Protective Factors’ must play a vital role where all involved with adoption are concerned. The significance of protective factors as guiding principles to aid in dealing with the risks inherent in transnational adoption can never be overstated and indeed should be underlined at every point. Naturally, these risks must be candidly discussed with prospective adopters by authorities and organisations, highlighting the important role of Protective Factors as a necessity for the positive development and outcome for transnationally adopted individuals. In the majority of cases, these protective factors were provided by the immediate adoptive family and notably the adoptive parents. However in a minority of cases, where adoptees perceived the family environment as threatening, they were dependent on other mentoring environments for protection and orientation.

The second trend, Social Networks, is seen to gain in significance for adoptees further along the axis of life. Responses indicated that these networks included their families, peer groups and friends (including other adoptees). While the protective factors are central to childhood years, supporting adoptees into adolescence, social networks as it appears from results, take on a leading part for accompanying young individuals through the labyrinth and turmoil of this next life phase. While many of the respondents’ social networks developed through their own social connections and interactions, other networks had been organised as a part of post-adoption programmes. The possibility of engaging in such specific exchange with youths of comparable background was welcomed by those who have experienced this opportunity. In the majority of cases, however, no such contact had taken place. Subjects have felt isolated even amidst the most loving of family circles. This inner isolation occurs as a result of having few if any connections with others who have experienced the same situation. In more general developmental terms, their situation and the inherent sensitive identity issues call for the company and empathy of peers. The transition period of adolescence is certainly one of ambivalence; elements of identity crisis paving the rocky path toward identity development.

The time factor for acknowledging and addressing the issue of adoption along the life-trajectory constituted the third trend. Although ‘Time Factor’ was not a specific theme in itself; apparent throughout all the main themes and sub-themes of the analysis was the issue of time and age as to when adoptees had begun to show interest in the issue of adoption and their own specific biography background. The subject of adoption appears to always be latently present, however the levels of awareness, interest and willingness to confront oneself with this topic varied considerably. Responses indicate that during the first years after adoption children are settling into their new families. For those adopted at very young ages, adoption is a pre-verbal memory; older children have more conscious and, sometimes vivid, memories. Issues such as sibling constellation, socialisation in kindergarten and school, as well as cultural environment also impact on the time factor trend.

For the majority of interview partners, the involvement with this study was the first time that they had been specifically addressed for information and their feelings about adoption. Articulation of these sensitive areas proved for some to be difficult, especially for individuals who had not as yet spoken to anyone apart from their family or friends about their life history. However, during the course of the interviews and by the responses elicited, it became clear that the subject was of great significance to respondents, even if this was not yet quite tangible. Of interest was the certainty conveyed by most respondents that their interest in the topic of adoption would gain in intensity the older they became.

The more settled adoptees were in themselves and also in their lives, the more it seemed they could afford to reflect on their biographies. An interesting detail from the photo contributions showed that only adoptees who seemed fairly settled in their teenage or young adult lives submitted photos of themselves as children. In cases in which respondents had become parents themselves (in all three examples these were mothers) having a child/children of their own had triggered and accelerated interest in their own adoption. The experience of parental responsibility, of deciding to ‘keep’ a child, blatantly confronts the adoptee once again with their own fate, even as in one case causing a re-traumatisation. In the other two cases there was indication that having a child contributed to a growing sense of inner security and strength, with these children constituting an anchor in the lives of their respective parents.

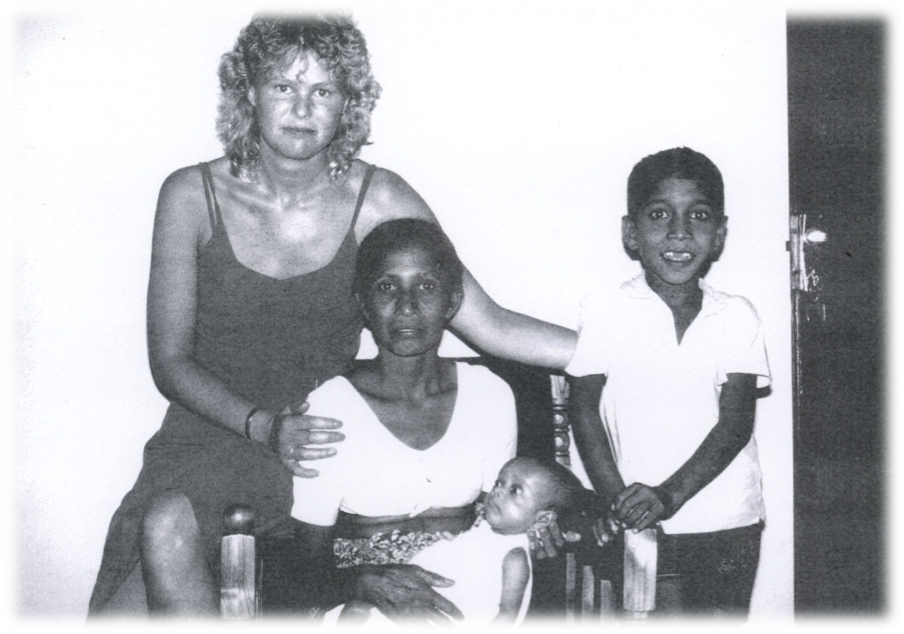

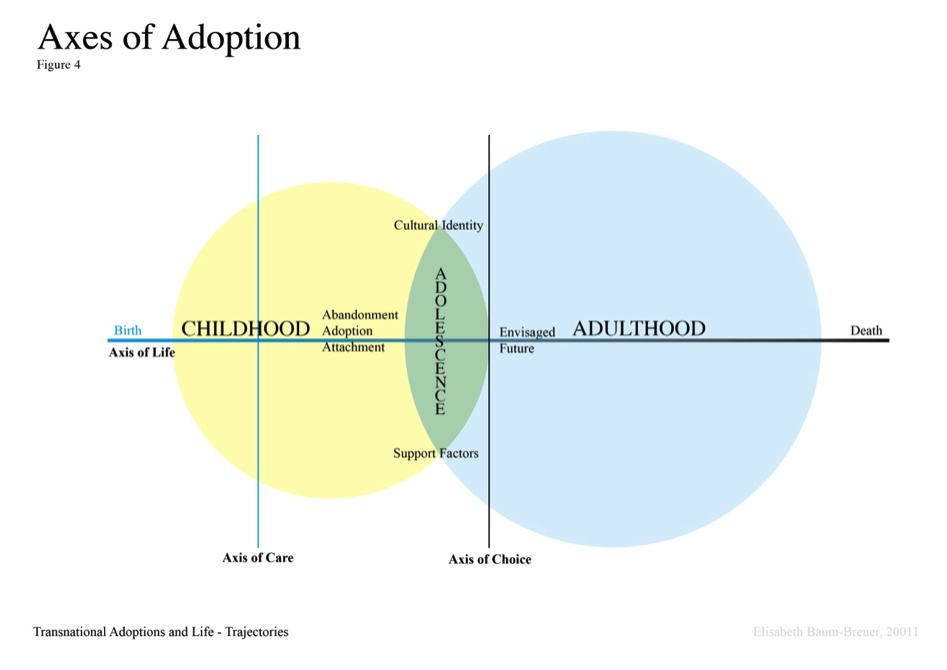

7. A stage-model for Adoption

The author developed a visual biographical research model "Axes of Adoption" to guide and structure the life-trajectory material derived in the research. Maalouf’s (1998) concept of horizontal and vertical heritage provided the theoretical background for this model, which allows for a detailed description and analysis of subjective phenomena.

Beginning with a ‘Life-Span’ approach to the development of an Interview Template (Axis of Life), the visual model includes aspects of Care and Choice based on Maslow’s (1973) Needs Hierarchy as being the two most important environmental influences for human development, depicted by two intersecting environmental axes (Axis of Care and Axis of Choice). In the final stage, the six major foreground concerns and themes derived from the interview material were applied. This model has the potential to sketch complex social interactions and to convey adoptees’ own experiences and messages, through which the practices of transnational adoption can be studied. It is the hope of the author that the graphic model may be useful for placing certain life stages and phenomena in perspective.

Figure 3: Axes of Adoption

8. Implications and conclusions

This paper notably points to the non-identified significance of including transnational adoptees in the discussion on crossover cultures, hybrid identity and global youth and their potential also as communicators, facilitators and translators between cultures.

References

Bohnsack, Ralf (2008): The Interpretation of Pictures and the Documentary Method. Forum Qualitative Social Research Sozialforschung. 9 (3), Art. 26.

Bhabha, Homi K. (1994): The Location of Culture. Abingdon and New York: Routledge Classics.

Esping-Andersen, Gösta (1990): The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press and Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hein, Kerstin (2006): Hybride identitäten. Bastelbiografien im Spannungsverhältnis zwischen Lateinamerika und Europa. Verlag: Transcript Kultur und Soziale Praxis.

Hugger, Kai-Uwe (2007): Verortung der Ortlosigkeit. Hybride Identität, Jugend und Internet. In: D. Villanyi, M.D. Witte, U. Sander, (Eds.) (2007): Globale Jugend und Jugendkulturen. Aufwachsen im Zeitalter der Globalisierung. Weinheim: Juventa.

Krüger, Heinz-Hermann/Marotzki, Winfried (2006): Handbuch erziehungswissenschaftliche Biographieforschung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Maalouf, Amin (1998): Les identites meurtrieres. Editions Grasset & Fasquelle (2000): Mörderische Identitäten. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.(1st Ed.).

Maslow, Abraham (1973): Psychologie des Seins. München.

Merten, Klaus (1995): Inhaltsanalyse. Einführung in Theorie, Methode und Praxis. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag (2. Auflage).

Selman, Peter (2009): The rise and fall of intercountry adoption in the 21st century. International Social Work 2009; 52 (5), 575-594. London: Sage Publications.

Smith, Jonathan A./Harre, Rom/Van Langenhove, Luk (1995): Rethinking Methods in Psychology. London: Sage Publications.

Weymont, Deborah (2006): „Black holes - mapping the absence" In: P. Harris (Ed.) (2006): In search of belonging. reflections by transracially adopted people. London: BAAF.

Über die Autorin

DSA Mag. (FH) Dr. phil. Elizabeth Baum-Breuer

|